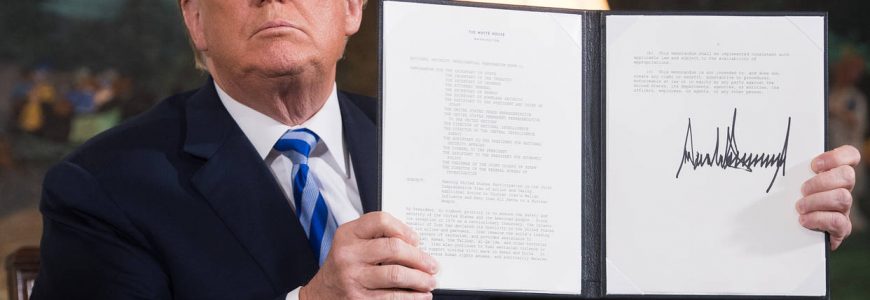

President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from the Iran nuclear deal and reinstate all U.S. sanctions won’t deliver punishing economic pressure capable of forcing Iran to submit to Washington’s policy demands. Along with diplomatic furor and a blow to nuclear arms control, the move also comes with damning unintended economic consequences for the United States.

The new U.S. policy involves snapping back all the sanctions on Iran that were removed in 2016 under the deal. Primary among them are the sanctions on Iran’s central bank and on its oil trade, the engine of the country’s economy.

Administration officials are betting that foreign firms that have invested in Iran and buy its oil will abide by the sanctions. They will also fan out around the globe to try to pressure foreign countries into joining the United States with measures of their own. Presumably the White House thinking is that the Iranian regime, once backed up against the wall, will capitulate or crumble.

This scenario is unlikely. Not every foreign company, bank, or oil trader will be inclined to comply with U.S. sanctions, particularly if their own governments are frustrated with the U.S. re-imposition of sanctions. There is no multilateral interest now in targeting Iran with financial pressure and diplomatic isolation, unlike during the 2012 to 2015 period of most intensive global sanctions on Iran.

Even when foreign firms are inclined to comply, many will be confused about how to do so. Explaining the rules to foreign banking associations, chambers of commerce, foreign financial and commercial regulators, and central banks takes an army of U.S. diplomats. The Trump administration has hollowed out the State Department’s ranks, and the department did away with its sanctions implementation office last year. Several key senior staff members at the Treasury Department, which is responsible for crafting and enforcing the sanctions, just resigned.

To be sure, some purchasers of Iranian oil will wind down their business to escape legal liability and out of grudging loyalty to the United States, a security ally. European refiners, which buy more than 500,000 barrels per day, will probably unhappily follow the U.S. sanctions rules. Japanese and South Korean purchasers, which together account for more than 500,000 barrels per day, will too. Even here, though, the effects may be delayed or softened as countries seek temporary waivers or exemptions.

But Iran’s biggest oil purchasers, China and India, may be less inclined to cooperate. They might even find opportunities to purchase additional barrels of oil from Iran, which has been pushing out more supplies in recent months. This could meaningfully diminish the effect of the sanctions.

When it comes to foreign banks and traders severing financial relationships and trade in goods with Iran, compliance will also be a mixed bag. European and Asian firms of any meaningful size will not tolerate the risk of violating sanctions and will stop dealing with sanctioned entities. These institutions, however, were already risk-averse and had minimized their exposure to Iran, so the effect of the new sanctions will be marginal at best. Meanwhile, some foreign banks insulated from U.S. jurisdiction could create bespoke facilities to sustain trade with Iran, even if they are hit with sanctions. There is precedent for this in China.