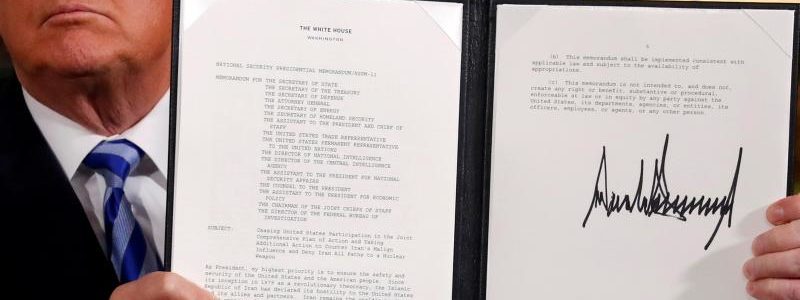

he Trump administration has no coherent Iran policy. In May, U.S. President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—the Iran nuclear deal—even though Iran was not in violation of it. Other than Trump’s uninformed and empty assertion that it was “the worst deal ever,” his pretext for the withdrawal was Iranian aggression in the region, which was not linked to the deal. In both his rhetoric and policy, Trump seems to be positioning the United States to enter into armed conflict with Iran, warning Iran in July that it could face “consequences the likes of which few throughout history have ever suffered before.”

Trump apparently wishes not merely to contain Iran’s power but to roll back its regional presence, confining its influence to its borders, disarming it, and, by implication, changing its regime, given that these are constraints that Iran’s government could not tolerate for profound strategic and ideological reasons. Doing so would take a massive effort and likely entail another American war in the Middle East—one that the president is not committed to fighting and would not have the popular support to pursue. Rather than a coherent strategy, Trump’s aggressive behavior reflects a strange and unhealthy obsession with Iran unwarranted by the actual threat it poses to the interests of the United States and its allies.

The risk now is that the United States could drift into a war with Iran in a fog of bombastic threats and jolting policy reversals even if there were no underlying interest in hostilities. But although Trump’s rhetoric is dangerous, his administration’s inordinate antagonism is rooted in a deeper inability, going all the way back to 1979, of the United States to find a way forward with Iran. It is time for Washington to do so before it is too late.

STRATEGIC ILLOGIC

The United States’ treatment of Iran as a serious strategic competitor is deeply illogical. Iran imperils no core U.S. interests. It refrains from attacking U.S. forces or using terrorism to target U.S. assets or territory, coexists with the United States in Iraq with little friction, and has agreed to limits on its nuclear program. Tehran scarcely reacts to Israeli strikes on its assets in Syria, where it maintains only a small forward-deployed force supplemented by ragtag Afghan, Iraqi, and Syrian Shiite militias. Iran is economically beleaguered and militarily weak, and its navy is a coastal defense force, capable of disrupting shipping but not of seriously challenging the U.S. Fifth Fleet or the battle groups in the Pacific theater it can call upon in a crisis. According to independent, informed assessments, such as the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ Military Balance, Iranian forces are plagued by outdated equipment, an inadequate defense-industrial base, and a large conscript army that is substantially undeployable on a large scale. Its air force flies planes incorporating 1960s technology, and it has virtually no amphibious capability.

Iran’s annual defense spending, about $16 billion, or 3.7 percent of GDP, on both measures falls considerably short of Israel’s, Saudi Arabia’s, or the UAE’s individually, and is positively dwarfed by their collective spending. Moreover, the United States’ military capabilities overwhelm those of Iran on every conceivable measure. Although those capabilities are intended to support the United States’ global interests, given U.S. forces’ astounding operational effectiveness, honed in continuous warfare in the Middle East and Central Asia since 2011, any serious Iranian challenge to U.S. regional interests that could not be contained through diplomacy would be easily suppressed, even if it morphed into a long-term, low-intensity conflict marked by persistent Iranian terrorism. But of course that is why diplomacy is such an attractive alternative to the use of force.

Iran does have some high-end military capabilities: it has deployed a 2,000-kilometer range ballistic missile, fields the advanced Russian-made S-300 surface-to-air missile system, and is thought to have substantial cyberwarfare capabilities. But the latter is an asymmetric asset, scarcely a match for its U.S. and Israeli equivalents, and Syria’s S-300s have not helped it defend against the Israeli Air Force, which destroyed its nuclear weapons infrastructure in 2007. Iran’s ballistic missile program would be a serious threat if it were coupled with mass production of compatible nuclear warheads, but this is a distant concern as long as the JCPOA remains in force. Overall, Iran’s ability to project military force in the region is severely limited. Iranian troops in Syria probably peaked at about 4,500, roughly equal to the 4,000 or so that the United States has deployed in the eastern part of the country. In Yemen, Iran’s military presence is even smaller. In Iraq, there is a residual Iranian military presence because Iran was a combatant in the war against the Islamic State (ISIS). Even there, however, it has reportedly inserted only around 2,000 troops to complement the Shiite militias that it supports, and these assets seem to be overmatched by the presence of an estimated 5,000 U.S. military personnel.

The Iranian intrigues that so alarm the Trump administration mainly boil down to its influence with the Iraqi government and support for Shiite militias, its ongoing reinforcement of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and its backing of the Houthi rebels in Yemen. Some would also throw in its support for Shiite groups in Bahrain, a vassal state of Saudi Arabia ruled by a Sunni minority. Yet Iran’s foreign policy has evolved essentially on the basis of opportunistic realism rather than especially aggressive revisionism, and, as noted, it has a sparse military presence in the region.

Iran, to be sure, is theoretically a problem for the United States in Iraq. But the United States created that problem by overthrowing the Sunni minority government of Saddam Hussein, ushering in a Shiite-dominated Iraq that would inevitably be subject to Iranian influence. Trump must of course deal with Iranian clout in Iraq, but U.S. strategic interests do not demand overriding Washington’s short-term need to stabilize the country. Recently, especially in the campaign against ISIS, the United States and Iran have been on the same side, and it appears that the Iraqi government has figured out how to work simultaneously with Washington and Tehran. There are still areas of clear U.S.–Iranian friction—Iraq, for instance, allows Iranian weapons to cross Iraq into Syria—but these are critical from Washington’s point of view only if Iran’s involvement in Syria poses a major threat to core U.S. interests, which it does not.

Iran’s geopolitical interests in Syria are obvious: Syria’s alliance with the Assad regime affords Iran a political toehold in the Levant and a logistical conduit to Hezbollah, its most important regional proxy—although “proxy” may not be the right word for a Lebanese political party whose coalition constitutes the largest bloc in the Lebanese parliament and is viewed by most Lebanese as a domestic political party with a nationalist agenda. Nonetheless, until the Trump team came in and became geopolitically more interested in Damascus, seemingly with an eye to forging a larger strategic partnership with Russia, the United States had seen fit to largely ignore Syria for decades. The Obama administration had initially hoped that Assad would fall but viewed Iran’s intervention as geopolitically unavoidable and insufficiently damaging to U.S. interests to justify a proxy war, which a U.S. humanitarian intervention against Assad would have entailed. In 2014, the rise of ISIS in Iraq and Syria prompted the United States to shift its focus in Syria from regime change to counterterrorism, and the U.S.-led air campaign that the Obama administration initiated in 2014 resulted in the marginalization of ISIS by the end of 2017—a result consistent with Iranian interests.